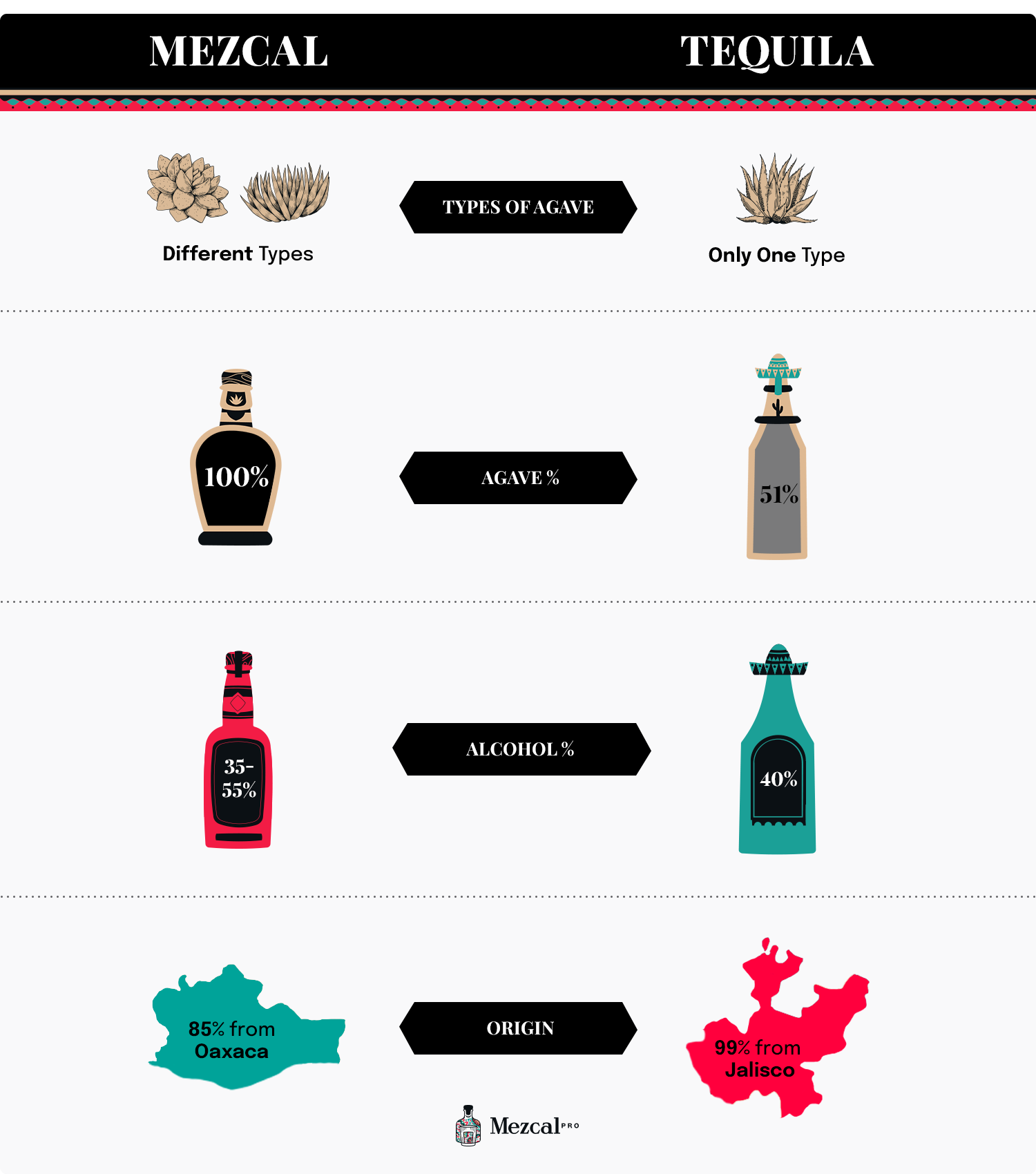

Both tequila and mezcal are distilled spirits made from the agave plant, a succulent of the lily family. The difference is that tequila is only derived from a single type of agave plant (Blue Weber), while mezcal can come from over thirty types.

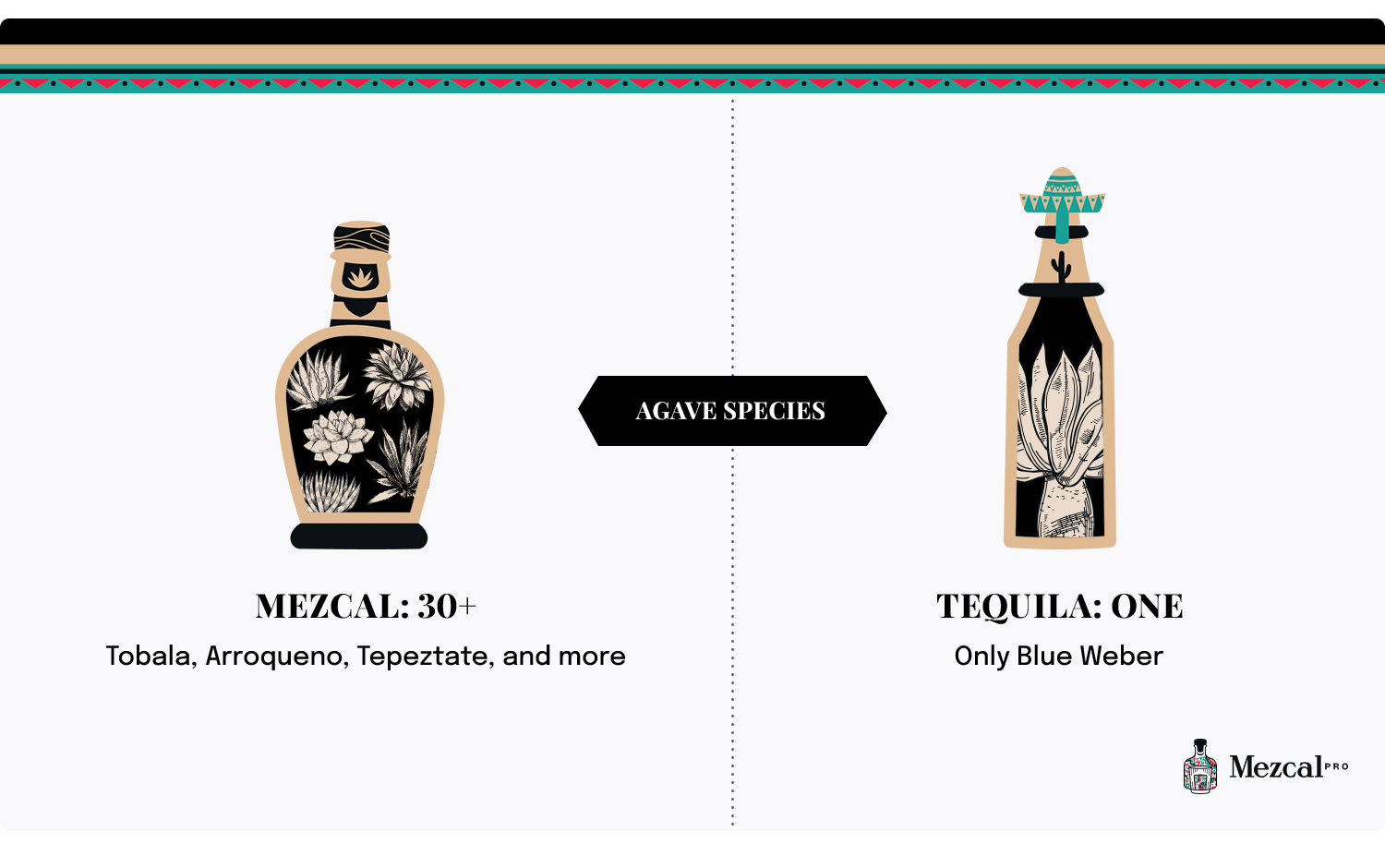

Agave Species

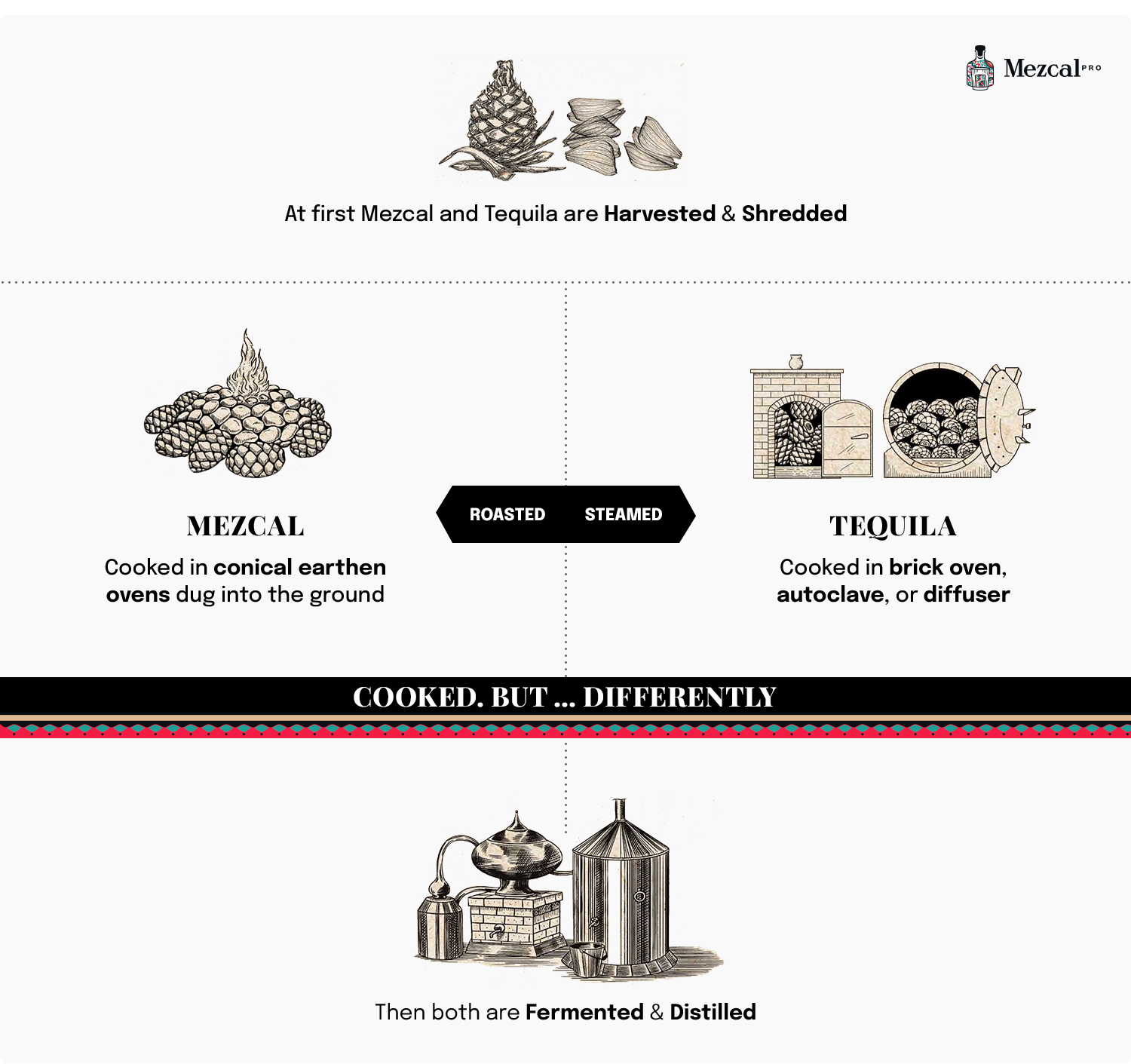

Both tequila and mezcal are derived from the heart (pina) of the agave plant, which is harvested, roasted or steamed, fermented and distilled. The species of agave used for each spirit has an enormous impact on the differences in flavor and aroma between mezcal and tequila. Since mezcal can be made from 30 different varieties of agave, taste and flavors between mezcals themselves can vary widely.

-

Tequila

By law, tequila can only be made from one type of agave, the blue agave or blue weber agave.

-

Mezcal

Around 30 different species of agaves are utilized. Out of the 252 species of agave, espadin agave (Agave angustifolia) is the most common type of agave used in the production of mezcal. About 90% of all mezcal production uses angustifolia as it takes the shortest time frame to mature, ranging from 4 to 8 years to reach maturity. This species of agave also adjusts well to most climates in Mexico and grows in a variety of wild and farm environments. Angustifolia also produces the highest yield of finished mezcal product compared to other agaves.

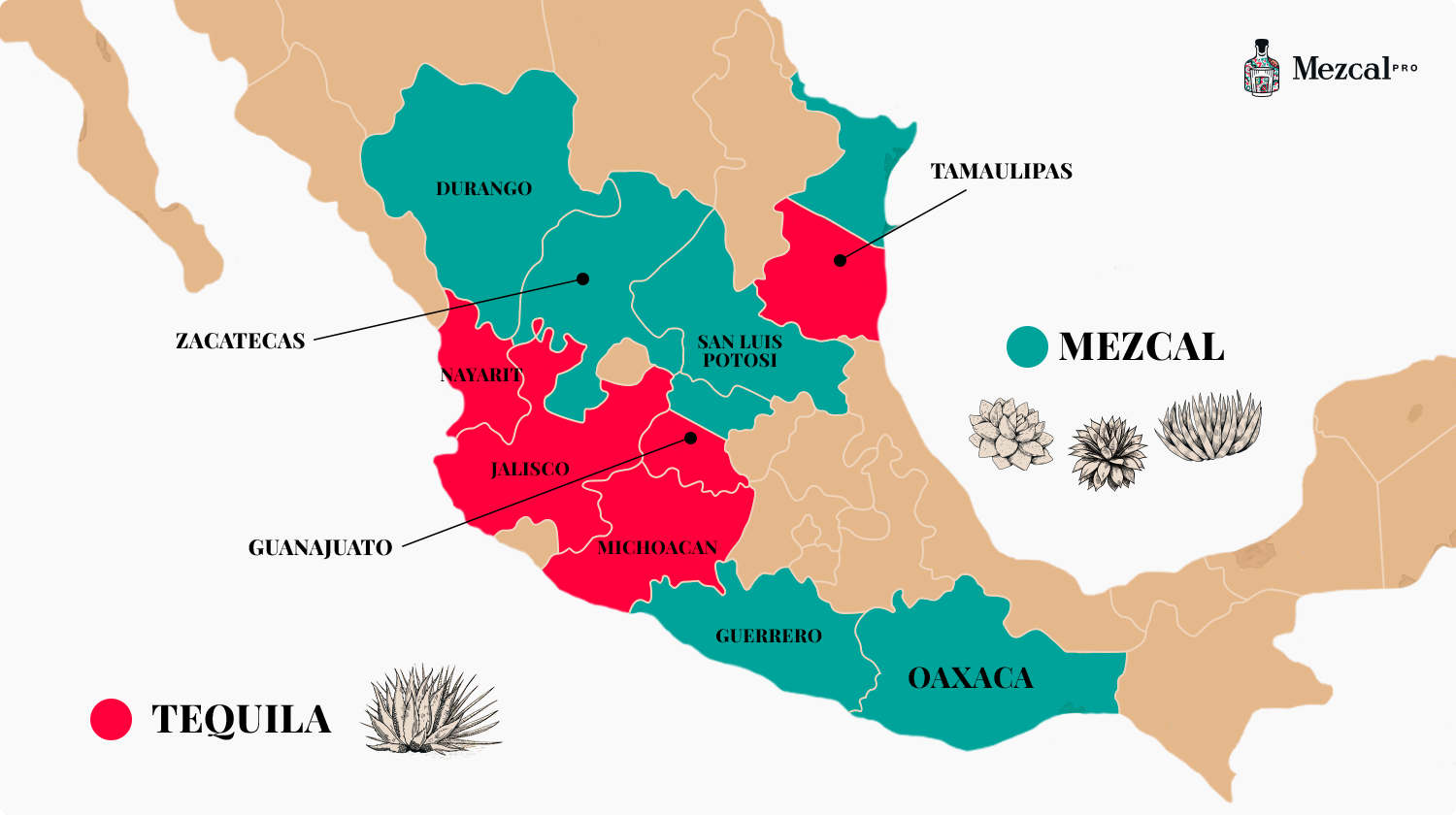

Origins

-

Tequila

While it can come from five different states within Mexico, Jalisco is home to about 99% of all tequila and remains the center of its production. The other four states involved are Michoacan, Guanojuato, Nayarit, and Tamaulipas

-

Mezcal

Mezcal’s origins span across nine Mexican states: Oaxaca, Guanojuato, San Luis Potosi, Tamaulipas, Guerrero, Michoacan, Zacatecas, Durango, and Puebla. Currently, about 85% or more of mezcal is made in Oaxaca.

In the past, mezcal was also known as vino de mezcal, or mezcal wine. Although unclear, it is believed that the distilling techniques were taught by Spanish conquerors some 400 years ago. The Mexican ancestors thought of “maguey” as sacred and considered mezcal to be from the gods, making it a drink that was consumed during cultural and religious events.

Production

-

Tequila

After the agave is harvested from the ground (killing the plant), the leaves are removed, leaving behind the agave’s heart or pina. These are then cooked in an autoclave, a large and stainless-steel oven. This cooking process softens the fibers and transforms the starches into sugar.

Once the cooked pina is crushed, it is fermented with the help of commercial yeasts and distilled two to three times in copper pots. Next, it is aged inside oak barrels resulting in one of three varieties depending on the length of aging. Blanco is aged for 0 to 2 months, reposado for 2 to 12 months, and anejo for 1 to 3 years.

-

Mezcal

After harvesting the pina of the plant, it is cooked in an underground earthen pit that is lined with charcoal, wood, banana leaves, and volcanic rock. After the pinas are dropped into the pit, a fire is lit, and the cooking process underground begins, a process that gives them a smoky and caramelized flavor.

Although traditionally roasted, there are some modern-day producers who steam the pinas to decrease the smokiness of the mezcal. Once the cooked plant is pulverized, releasing its cooked liquid, it is left to naturally ferment. Finally, the liquid is distilled in clay pots. Mezcal can also aged in oak barrels and grouped based on their aging process. "Joven" mezcals are aged for 0 to 2 months, reposado for 2 to 12 months, and anejo for at least one year.

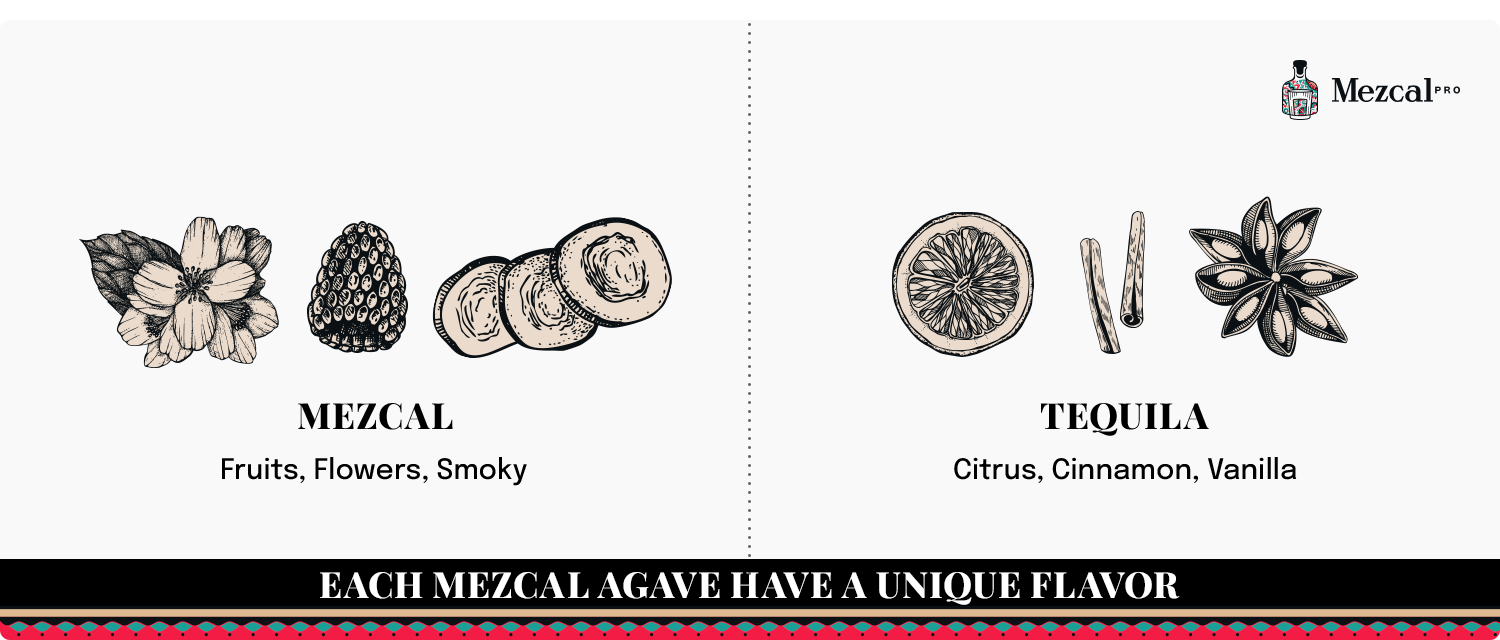

Taste, Flavor, and Alcohol By Volume (ABV)

-

Tequila

Generally, tequila blanco (unaged) has a strong agave flavor with hints of pepper, citrus, and spice. Tequila reposado is often smoother with notes of caramel, vanilla, and oak. Tequila anejo is rich with tones of cinnamon and vanilla, the most suitable for drinking straight. Tequila is usually about 40% ABV.

-

Mezcal

Due to its preparation underground, mezcal has a range of smokiness that can be light to heavy. Mezcal flavors can range from sweet, fruity, peppery, vegetal, and earthy tones.

The most crucial factor that determines the flavor of mezcal is the type of agave chosen and how it is prepared by the master mezalero. Small details like can have an enormous impact on the final flavor, like what the agave is cooked with, how the liquid is fermented and distilled, and which vessels they are prepared in. Mezcal ranges from 35% to 55% ABV.

Types of Mezcal

The production of mezcal is regulated by the mezcal regulatory council, or Consejo Regulador de Mezcal (CRM) which categorizes the finished product into one of three buckets based on how the mezcal was produced. The categories are:

The most popular variant produced by most large distilleries, mezcal is produced using advanced equipment such as autoclaves, diffusers, stainless steel tanks, and more. This advanced equipment allows mezcal to be produced at a large scale.

Mezcal artisanal is produced by distilleries using less advanced processes. These producers use clay ovens and open pits for roasting the pinas, a tahona (giant stone wheel drawn by a mule or donkey) to break down the cooked agave, and hollowed tree trunks or concrete tanks for the fermentation process. Distillation can be done using copper, clay, or steel pots that sit directly on fire.

Mezcal ancenstral must be made of agave cooked in earthen pits and milled with a tahona, Egyptian mill, or hand mallet. For fermentation, the process must take place in animal skins or vessels made of clay, wood, or concrete. Once ready, it is distilled using clay pots over an open fire.

Mezcal vs Tequila: History in The United States

With roots reaching back into pre-Hispanic times, mezcal's development from traditional beverage to modern spirit was turbulent. Mexico’s war with the United States in the 1840s exposed American soldiers to tequila for the first time. The first export of tequila to the U.S. is believed to have been in 1873 when Don Cenobio Sauza sold three barrels to El Paso del Norte.

Tequila's growth really started taking off in the 1880s with the drastic expansion of railroads. In the late 1920s, Prohibition in the USA surprisingly boosted the popularity of tequila resulting in mass smuggling across the border. During World War 2, it again rose in popularity as spirits from Europe became scarce.

Decades later in the 1980s, the increasing number of American tourists to Mexico led to a subsequent increase in exposure to tequila. Tequila became a status symbol, rising from casual party drink to a high society luxury. Tequila's fame continued to grow in 1983 when Chinaco, the first premium tequila began to be distributed in the US. Tequila has since continued to grow in fame and popularity, amongst both casual drinkers and seasoned aficionados.

Tequila had a massive head start over mezcal in terms of exposure to the US market. Mezcal is still a particularly niche product with only a fraction of the fame and sales volume of tequila. Mezcal's growth in the US began with Ron Cooper, the founder of a brand called Del Maguey. While on a trip to Oaxaca to create art, he followed rumors of mezcals made by farmers on remote palenques only accessible through dirt roads. He loaded up his truck with mezcal samples and attempted to cross the border. Unfortunately, U.S. customs only allowed one liter across the border and he had to relinquish his haul.

He then started to export artisanal spirits made by family palenqueros in villages where most have been producing mezcal for generations using ancient practices. His company soon became the first producer to credit the village the mezcal was made, creating the "single-village" designation. As more travelers from the US visit Mexico (and in particular, Oaxaca), mezcal's fame continues to grow.